|

After travelling to Khulna and Bagerhat District in the south-west, and Bogra in the north (where people mainly suffer from floods, though Khulna and Bagerhat are also affected by cyclones and salinity intrusion), my last Field Trip goes to the South Coast, to Patuakhali and Barguna District.

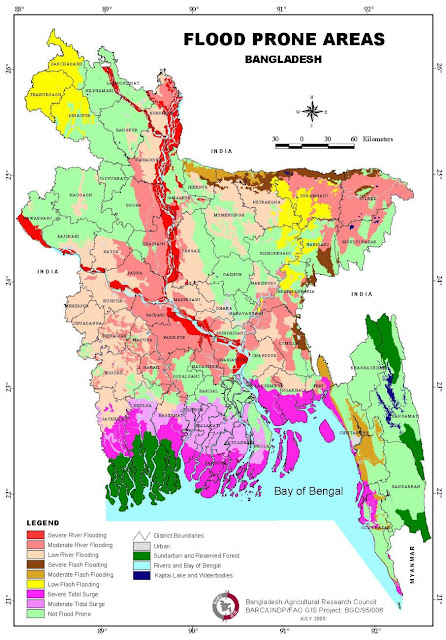

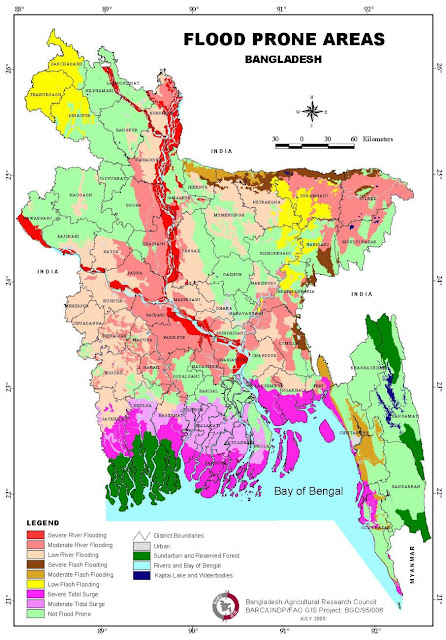

(The bigger picture of flood hazards in Bangladesh can be found here.) |

|

| We start from Dhaka by launch, following the river Padma on its way to the Bay of Bengal. |

The launche terminals are lound and lively, busy places. Most people just stay on the deck over night, sleeping crowded together on the floor - but following the anxious safety advises of our Bangladeshi colleagues, we agree to booking a private cabin for 1000 Taka.

|

Me and my travel-mate Will Smith from London (also a Visiting Researcher at ICCCAD - and yes, that's his real name) agree that this is the most comfortable way of travelling.

We can enjoy a nice dinner and very nice sleep befor arriving in Amtali the next morning. |

|

| In Amtali, we meet staff memers of the local NGO Nazrul Smriti Sangha (NSS), who are implementing an adaptation project funded by Oxfam. |

|

| Under this project, the women of Angulkata in Amtali Upazila have formed a Community-Based Organisation to conduct need adssessments, choose which memebers should get financial support from NSS, and monitor the project activities. |

|

| NSS Programme Director Shahidul Islam shows a Risk Map developed by the community, including all households, water supplies, mosques and shelters in the village. |

|

This school is working as cyclone shelter in times of a disaster.

Bagladesh was hit by three big cyclones during the last years.

Losses and casualty numbers of Sidr in 2007 were extremely high. When Aila struck only two years later, many people were very vulnerable due to their insecure housing situation as a result of Sidr. At the same time, awareness had increased, and many lives could be safed.

Mahasen in 2013 made landfall in the morning, when people were already awake, had recieved information about the upcoming storm, and made the necessary preparations to store their valuable items safely, and seek shelter.

Islam tells us how impressed he was when he visited Angulkata just hours after the cyclone, and found people busy with their daily work, as if nothing had happened. |

|

However, Mahasen destroyed all of the crops that year. Without savings, it is impossible to cope with cyclones.

NSS has provided selected community members with ducks and cows, and trained the women of Angulkata on how to connect with the local market, and how to bargain with their customers to ensure a fair price for eggs and milk. |

|

The strenght and awareness of these women is incredible.

Hawa is only 20 years old. She was married when she was 16, after attending only 10 years of school.

She is super informed about the causes and effects of global warming, and gives a very easy solution: "Those who are cutting the trees, they could make sure to at least plant to new trees before cutting one." |

|

| The women in the villages of Amtali unanimously say: "We don't want to migrate. We want to stay here, where our families have lived for centuries, where our home is." |

|

| But everyday live is a challenge. Monsoon season is starting later and later each year. The communities run out of fresh water resources during the long summer. This is not only impeding agricultural activities, but also causes health hazards. |

|

| Maniral Sultana, Technical Officer at NSS, tells me that water shortage is mainly affecting women: They are responsible for supplying their families with water, for cooking and childcare; and they are also facing hygienic problems if they cannot wash themselves. |

|

In Angulkata, NSS has helped the women to excavate a pond to collect rainwater, and to build a cubicle box with a water pump. "For women only", they tell me proudly.

Bathing in a pond together with men in considered inappropriate - not to speak about taking off your cloths to wash them, or properly wash yourself! |

|

Together with Manira, the women have developed an Annual Plan for the activities they want to undertake to adapt to cliamte change:

Approach the local government to finally include the community in the budgeting process, as required by law. Participate in training on how do prepare for disasters, or how to bargain for fair prices on market. Allocate khash land, and decide about which households should get what kind of inout support, like ducks or cows, from NSS.

The biggest problme, as usual, is the lack of money. |

|

When I ask about the responsibility of countries like Germany to help them, Rahina Begum from the village Uttar Parikata literally shouts at me: “I am blaming

you, the developed countries. I’m blaming you, because you are responsible. You

are responsible to help us.”

There's literally nothing I could bring up against this argument. I tell her that I agree, but that all I can do is to report back to my country how she feels, and try to make people understand - and act accordingly.

|

|

Next day, we visit another NGO, named WAVE, in Patuakhali, only a 40 minutes bus ride away.

|

|

| The village Boro Awliapur is also suffering from ever-longer summers, and lack of rainfall. More than 200 of the 345 families in this village have been categorised by WAVE as "poor" or "extreme poor". |

|

Afiqul Islam Mizan, a rice farmer from Boro Awliapur and member of the Union Parishad (the local government) tells us that one kind of rice paddy, aus, already got extinct in the area. "Climate change is affecting our total life", he says.

Both land owners like him and day labours and fishermen are suffering from the shortage of water.

The only solution many people see is migration: Trying to find work in Dhaka or other cities, either temporarly or permanently.

Afiqul has a very precise understanding of who should come for help: The Bangladesh Waterboard for canals and irrigation system, the Department of Agricultural Extension for drought-resilient crops, the Youth Development Centre in Patuakhali for skill training for adolescence, NGOs for input supply for the poor. And the community members themselves for getting organised to demand this support.

"We have formed a community group to have unity", he says. "If we are united, we can address the problem."

They have set up a shared bank account to collect money for times of disasters, to help each other out. But Afiqul also points out the responsibility of developed countries: "You are beating me. That’s what causes the

health hazard. So, first, you stop beating me. You understand? Stop the greenhouse effect. Then assist us."

|

|

During a little tour around the village, I can see how much of a difference a tiny amount of money can make for a whole family's live.

Shadidul Akando was seriously ill last year, lying in hospital, with his wife Shahida and their three daughters struggeling to survive. The family is landless, and had no income opportunity.

WAVE helped Shadidul to set up a little shop, where he now sells self-made snacks. "In the future, we hope we can upgrade our business, and eventually have a homestead of our own", he says. |

|

Rani means "queen" in Bangla - but Urmila Rani is a widow who has to pay school fee for her adolescent daughter, but used to earn only 1800 Taka a month working as a helper in a sewing shop.

WAVE has provided her with a sewing machine and a small stall, in which she has set up her own sewing business.

"I had the skills to do it", she tells me. "All I needed was some bookkeeping training, and the start-up capital."

Now she can make up to 4000 Taka a month during the season of Muslim or Hindu festivals, when people like to order fancy Sarees and dresses.

Urmila is also teaching her 16 year old daughter how to sew. The Ranis can now create their own Sarees - to look like a queen, at least. |

|

On the way back to Dhaka, wich is also the beginning of my way back home, I think about how easily we spend money worth the 14 000 Taka WAVE is granting to each "beneficiary". 160 Euro - that's one Saturday morning of shopping clothes, or one fancy dinner wih the whole family.

How easily we could stay at home to cook, or go to a second-hand market for cloths, and use these 160 Euro to help a whole family change their whole life...

Yes, there is always this issue of "will they make the best out of it?" and "How to make sure the money is not wasted?"

I think daring to waste a jeans and a jumper to give someone the chance to start a new life could actually be worth a try. |

What will I take home from five weeks in Bangladesh?

1) Offer my help to foreigners and lost-looking people whereever, whenever. After having recieved to much kindness, help and hospitality, I really want to give something back.

2) Stop complaining about trivial things, and take the incredible smart and strong women of Amtali as role models for how to connect and act collectively in the name of change and social justice.

3) Try to come back to Bangladesh again one day soon - but learn Bangla first!

And what is my conclusion on the topic of Community-Based Adaptation?

1) Adaptation to climate change is a tricky thing: There are so many issues, challenges, contradicting interests. Can it ever be "successful"?

2) People like Hawa and Rahina, Shadidul and Urmila: They don't have a choice. They have to try to adapt as best as they can. And I think we have a responsibility to support them as best as we can.

3) It is important to keep in mind the limitations of adaptation. River erosion and sea level rise permanently displace people. There is no way to adapt on disappearing land. This is where adaptation ends, and loss and damage comes in. The upcoming Conference of the Parties in December in Paris will hopefully, finally address this issue. We do have - at least in theory - the responsibility of "developed" countries to support people in Bangladesh, it's enshrined in the UNFCCC. We now need to think about what to do with those who cannot stay, and need to find a new home - cf. point 1.